Ignored No More—Indigenous Voters May Be The Difference In 2024

The major political parties are taking notice of Indigenous voters, especially in swing states.

According to the last major United States census in 2020, the Indigenous American and Alaska Native (AIAN) population in the United States was 9.7 million people—2.9% of the total population.

This is a significant increase from 2010 as more culturally sensitive approaches were adopted for outreach to communities of color, who have always been under-reported. The National Urban Indian Family Coalition (NUIFC) worked in conjunction with census officials to build bridges to NDN Country*.

*NDN Country or Indian Country is a term Indigenous Americans often use to describe the Native populations of the United States and Canada

Actual numbers are still likely higher as Indigenous peoples around the globe rightfully distrust government actions and often resist participation in “counts.” Identifying themselves to the government in the past led to tragedy and loss in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand…

Just know, for any Indigenous population numbers gathered by a colonized country or territory, the actual numbers of Indigenous people there are higher.

But basing decisions on just census numbers, Indigenous peoples have long been the voters ignored in the United States by the major political parties.

However, beginning in 2018, the parties noted Native voters could swing local, state and national elections.

Before discussing the implications of this, we must first understand that Indigenous peoples in the United States have only had the right and access to vote for less than 60 years.

Native Voting Rights

Despite living on their own homelands, Natives were not allowed to vote until the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act.

However, in order for most Indigenous people to vote under this law, they were required to renounce their tribal citizenship and leave tribal communities.

As just another land grab and method of forcing assimilation, the 1924 law wasn't meant to be for the benefit of Natives.

Most states with high Indigenous populations passed laws barring any Native living on a reservation or designated Native land from voting. Indigenous peoples in the United States didn't all get the right to vote until 1965's Voting Rights Act.

There are Indigenous elders alive today who remember when they and their families weren't able to vote 60 years ago.

This voting ban was especially ironic in two ways.

The very concepts of American democracy were gleaned from the structures of two major Native tribal confederacies: the Haudenosaunee Confederacy of the Northeast woodlands and the Powhatan Confederacy of the Chesapeake Bay region.

The framers of the United States Constitution were looking for examples of individual, somewhat autonomous governments working collectively in a larger nation as a means to join the former British colonies into one nation without losing their current independence. Despite what most people learn in school, neither Ancient Greece or Rome, nor the Magna Carta gave them a framework to follow.

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy, however, joined five independent tribal nations—which later expanded to six—into one cooperative collective. Tribes of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy were Kanien'kehà:ka (Mohawk), Onyota'a:ka (Oneida), Onoñda’gegá (Onondaga), Gayogo̱hó꞉nǫʼ (Cayuga), Onöndowa'ga:’ (Seneca) and Skarù:ręˀ (Tuscarora).

The Haudenosaunee constitution developed in the 12th or 13th century is the Kaianere'kó:wa or Gayanashagowa—the Great Law of Peace. The Law of Peace includes its Chiefs, Clan Mothers, and Faith Keepers, the delegates that form the three regulatory bodies of the confederacy.

It was overseen by these three separate branches offering checks and balances, with one overseeing overarching decisions and daily logistics, another handling proposed changes in resource distribution and laws, and finally a branch granted the ability to overrule the other two for actions or decisions not in the best interests of all or in violation of the existing primary agreement.

Sound familiar?

The Haudenosaunee also gave each person who had reached the age of majority an equal vote in elections and confederacy decisions. Of course, the all male, all White, all privileged Constitutional Congress changed that bit to all White, male, landowners got an equal vote.

The other irony was this: Despite being denied citizenship or voting rights, Indigenous peoples volunteered and fought for the colonies and later the United States in every war since the American Revolution. Natives, by percentage of population, have the highest rate of military service in war and in peacetime.

The Indigenous Code Talkers of WWI and WWII—Navajo, Cheyenne, Comanche, Meskwaki, Kiowa, Winnebago, Chippewa, Creek, Cherokee, Lakota—who helped the United States establish unbreakable codes, came home and were still denied the right to vote if they stayed in the tribal communities where they learned the Indigenous languages used to develop those codes.

Idle No More

The political parties of the United States finally took note of Indigenous voters in 2018 after NDN Country took note of changes in Canada brought about by the First Nations “Idle No More” movement.

Idle No More began in November 2012 as a grassroots protest against Bill C-45, a controversial omnibus bill that threatened Indigenous rights and the environment.

Four women from Saskatchewan—Jessica Gordon (Pasqua), Sylvia McAdam (Cree), Sheelah McLean (non-Indigenous), and Nina Wilson (Nakota and Plains Cree)—began the movement after exchanging emails about Bill C-45 and creating a Facebook page with the name "Idle No More."

The hashtag #IdleNoMore took off online and soon created a major voting and activism bloc that eventually swung the vote for prime minister in 2015. The blueprint for Indigenous organizing online was set.

Indigenous peoples throughout the Americas followed their lead.

They used #IdleNoMore and their own hashtags to organize global water, land and air protection efforts against actions like the Dakota Access Pipeline, Keystone XL Pipeline, Amazon mining and deforestation, building a telescope on Mauna Kea, bulldozing sacred sites and endangered habitats for a wall, etc…

And in 2016, the first concerted, unified, national Indigenous voting push was visible across Native Twitter, on Facebook, and Instagram.

Native artists like Steven Paul Judd (Kiowa and Choctaw) created artwork for organizations like the Native American Rights Fund and Native Organizers Alliance. By the 2018 midterms, regional, state, and local Indigenous voting initiatives were organized largely through their social media.

These efforts saw dividends as the first two Indigenous women were elected to Congress—Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) and Sharice Davids (Ho-Chunk).

Davids would be reelected in 2020 and 2022, while Haaland would be chosen by Democratic President Joe Biden to be the first Indigenous person to hold an appointed cabinet seat as Secretary of the Interior.

The Department of the Interior encompasses the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and the National Park Service (NPS).

Under Haaland, Charlie Sams (Cayuse and Walla Walla, enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla) became the first Indigenous director of NPS.

Reactions To Donald Trump

Little good came to NDN Country under Republican President Donald Trump during his reign from January, 2017 to January, 2021. One benefit, however, was an energized electorate, including in NDN Country.

The 2018 election saw the creation of more Indigenous rights organizations, like Illuminative, that included voting as a specific focus.

Through eye-catching social media posts, they offered voting guides online, tips on organizing locally, and amplified deadlines for registration, early voting, and absentee ballot requests.

Record numbers of Indigenous voters turned out to vote in 2020.

Some even wore their Indigenous voters swag designed by artists B. Yellowtail (Northern Cheyenne and Crow) and Steven Paul Judd.

Ignored No More

Recognized as an influential voting bloc by the 2018 midterms, the major political parties reacted in different ways to Indigenous voters.

The Democratic Party, which had a history of some outreach to Indigenous communities, increased its efforts and took steps to recruit and support Indigenous candidates.

Nationally, Davids and Haaland had the Democratic Party's backing.

At state level, Peggy Flanagan (White Earth Band Ojibwe) was elected Minnesota Lieutenant Governor as Governor Tim Walz's running mate in 2018 and reelected in 2022.

Flanagan became the first woman of color elected to statewide office in Minnesota and the highest-ranking Indigenous woman in elected office in the United States.

If Walz wins the vice presidency with Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris, Flanagan will become the first Indigenous woman governor.

The Republican Party chose a different approach.

New voter suppression and registered voter purges were enacted in GOP-controlled states with many of the changes directed at BIPOC voters.

One method of suppressing Indigenous votes was through voter ID laws that specifically disallowed the use of Tribal ID cards. States with high Native populations like North Dakota demanded “street addresses” be required for proper identification, knowing many reservations do not have streets.

Another method was closing polling places near areas of dense BIPOC populations. For many Indigenous voters, this meant their next trip to the polls would take hours.

Many point to changes to the federal Voting Rights Act. The United States Supreme Court struck down a section of the act that forced some counties and states to get clearance before changing election procedures to protect against discrimination—like closing polls in minority communities.

Since the 2013 SCOTUS ruling, Republican voter suppression efforts have increased.

Voting rights attorney Patty Ferguson-Bohnee (Pointe-au-Chien)—director of the Indian Legal Program at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law—noted:

“Now you can pass all kinds of laws without being precleared. There’s been an erosion of voting rights over time … and it’s really up to Congress to do something.”

Despite the GOP's best efforts, the Navajo Nation helped flip Arizona blue in 2020.

Natives Can Be The Difference In 2024

Back in 2023, it was already being projected that Indigenous voters were a major factor to be considered in 2024. Record Indigenous voter turnout changed Arizona's presidential election outcome in 2020.

NPR reported the projected 5 million Native and Alaska Native-identifying 2024 voters in both rural and urban communities was expected to be an underestimation of the potential impact.

Jacqueline De León (Isleta Pueblo), a senior staff attorney at the Native American Rights Fund, said:

“Native Americans are incredibly influential and have the ability to really swing those elections on the margins.

Both political parties have been really negligent when it comes to the Native American vote. Often there is an unfamiliarity.

There's a fear of approaching Native communities that may seem unapproachable or there's uncertainty over how to approach Native communities. And so there just hasn't been an investment.”

NPR predicted the Native vote would impact 2024 races for Congress, Senate and President in:

Alaska - currently red

Arizona - identified as a swing state

Michigan - identified as a swing state

Montana - currently red

Nevada - identified as a swing state

North Carolina - identified as a swing state

Wisconsin - identified as a swing state

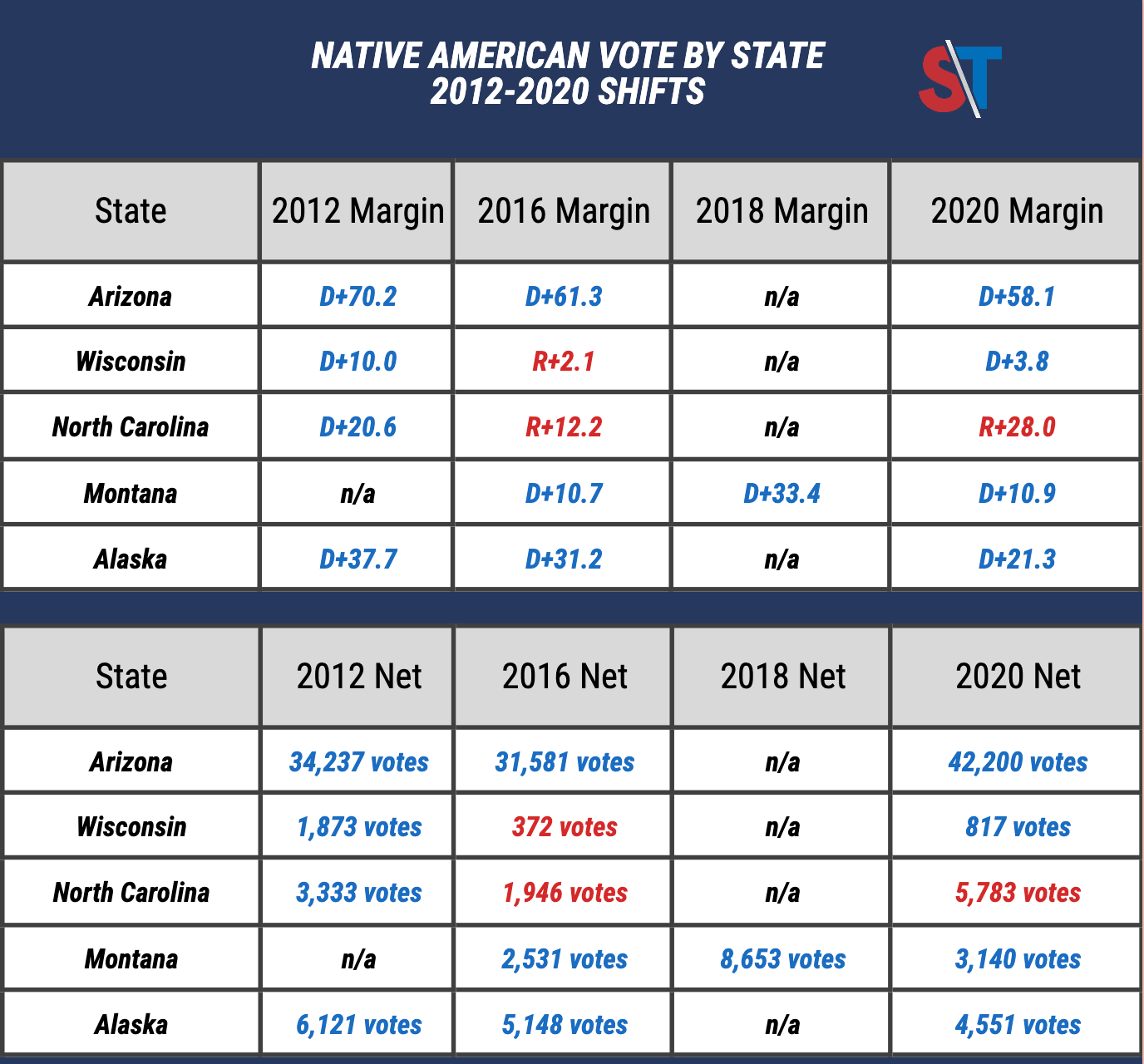

Split Ticket analyzed the shift in the Indigenous vote from 2012-2020 for the five states with the largest Indigenous voting blocs.

What's Ahead

While the GOP continues to try to disenfranchise BIPOC voters, NDN Country has been preparing for the 2024 election in big ways.

The National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) launched the Native Get Out The Vote campaign: “Honoring the Past; Preparing for Our Future.”

NCAI President Mark Macarro (Pechanga Band of Indians) explained:

“Our goal is to excite our fellow American Indian and Alaska Native people to vote and to support a ‘Sovereignty Ticket’ of key issues vital to Tribal Nations and their citizens.”

NCAI National Advisory Council on Indian Education member Dr. Aaron Payment (Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa) added:

“We want all Natives, young and old, to vote. We stand to be the margin of victory in key battleground states.

We intend to play a role in shaping policy that relates to us. While we recognize the 100th anniversary of the passage of the so-called ‘Indian Citizenship Act’, we still have challenges with voter participation and voter suppression.”

NCAI's website offers 2024 Sko Vote Den* toolkits.

*Skoden is common Indigenous slang in the USA and Canada for “let’s go then.” It's often heard with “stoodis” for ”let's do this.”

The National Urban Indian Family Coalition (NUIFC) is continuing its "Democracy is Indigenous" campaign as they have in every election cycle since 2018.

Executive Director of NUIFC Janeen Comenote (Quinault) stated:

“Every vote in our communities is not just crucial; it's a powerful catalyst for change. Native voices are increasingly becoming decisive factors in local elections, shaping the political future at every level. Our engagement in the United States political fabric is not just significant; it's revolutionary.

We are not only making the invisible visible; we are paving the way for a future where Native representation is undeniable and influential. Over the last 15 years of working with urban American Indian communities, we've seen that those with active Native participation don't just participate in the civic landscape of America—they lead it.”

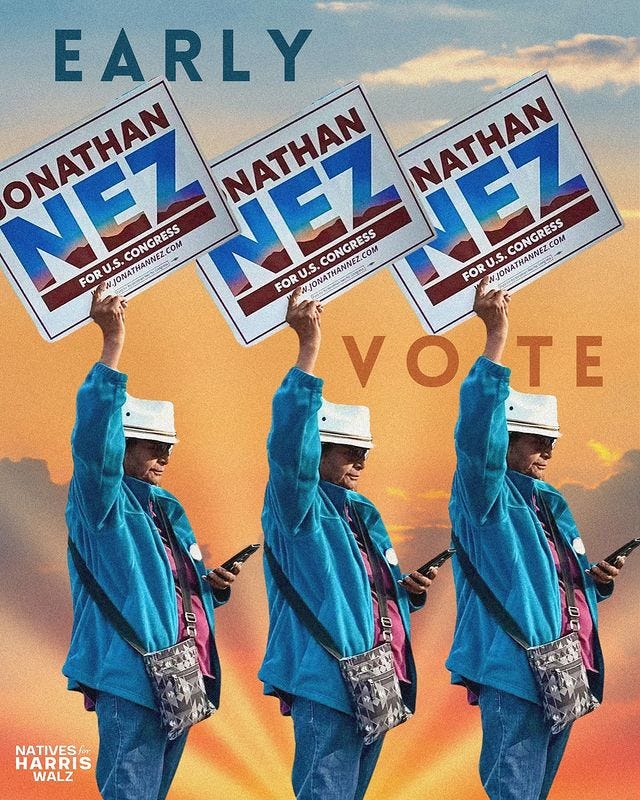

In Arizona, Jonathan Nez (Diné) is vying for a seat in Congress.

According to ICT News, here's 2024 by the numbers as of May:

140 Indigenous candidates running for public office in 23 states

12 candidates running for Congress

58% of candidates this election cycle identify as women

40% identify as men

2% identify as Two Spirit or nonbinary

93 Democrats; 27 Republicans; 20 independent/nonpartisan

Recognizing that “red” states are trying to make voting harder, Protect the Sacred and Diné activist Allie Redhorse Young started Ride to the Polls to register voters and get Indigenous youth to vote.

It hosts events using horses, bikes, skateboards and feet—in a “Walk to the Polls” event—to emphasize the importance of getting to the polls and voting.

The 3-mile Walk to the Polls celebrated 100 years of Native American citizenship in the USA and honored the Navajo Long Walk, when the tribe was forcibly removed from its homelands in the 1860s.

Actor, activist, and Indigenous rights ally Mark Ruffalo and Indigenous descended Colombian and Venezuelan American actor Wilmer Valderrama attended the Walk to the Polls event.

Ruffalo has been a very vocal advocate for Indigenous peoples for years.

He stated during the event:

“[The United States] is a nation that has been horrible to these people, but it was a nation that was built on the idea that it was for all of us.”

Noting Secretary Haaland and increased Hollywood representation and visibility, Ruffalo added:

“[Indigenous Americans are] being seen in our media and movies and television and our storytelling in the way that they deserve to be seen. And their wisdom is being honored, and their power is being recognized through voting.”

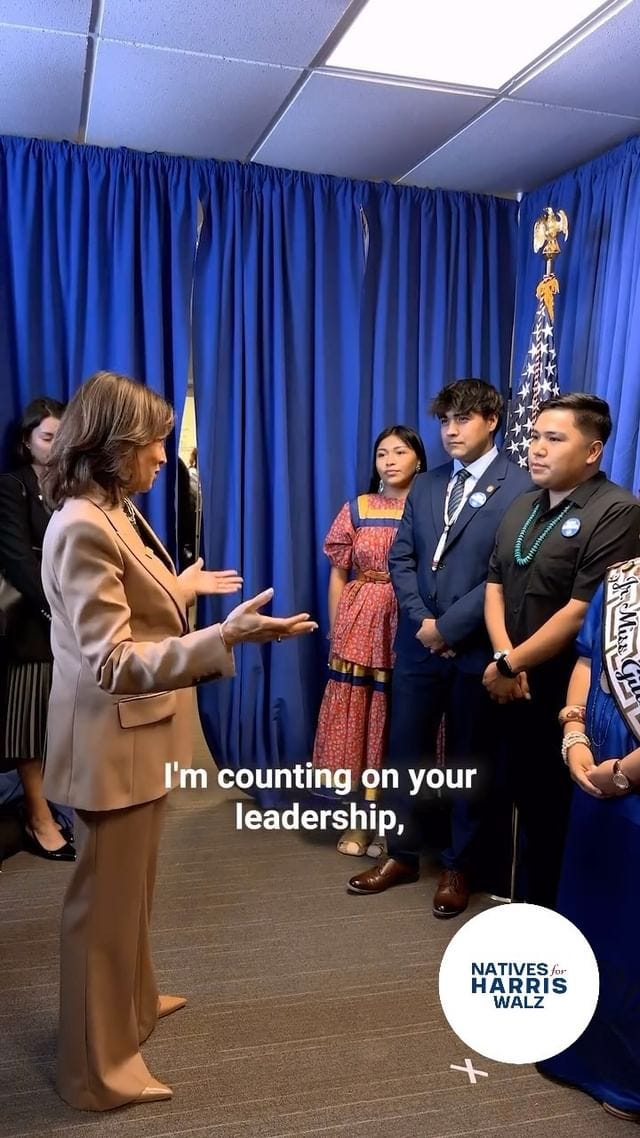

And speaking of Deb Haaland, she’s hit the campaign trail in person and online.

Secretary Haaland addressed the Democratic National Convention and stated voting is sacred.

She spent time with Lt. Governor Flanagan speaking with voters at the state fair in Minnesota.

And she has taken to TikTok to reach voters and encourage them to get engaged.

And that's what we all need to do, regardless of our voting demographic.

Get involved, get engaged, and get to the polls.

Skoden. Stoodis!

~~~~~~~~~~

Well written and very informative, I didn’t know that it took until 1965 before those still living on reservations had the right to vote! I am glad that there is Democratic outreach, and I can imagine Secretary Haaland’s messaging will help.

What great reporting.