We've Got A Supreme Court Problem

The Supreme Court is out of control, it's time for Congress to step in with real reforms and ethical accountability.

The approval rating of The Supreme Court has plummeted to historic lows, now consistently below 40%, with disapproval sometimes as high as 60%.

According to Gallup, as of about a year ago, 40% was the lowest approval rating they had clocked for the Court.

When did it hit that record low?

The court’s approval rating first fell to the record-low 40% in September 2021 after it declined to block a controversial Texas abortion law, a precursor to its 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision that overturned Roe v. Wade.

Now with an average approval rating of 34%, that former record low looks like a high watermark by comparison.

The Court’s radical rulings, including the June 2022 Dobbs decision, are certainly part of the story. But as conservative Justices repeatedly flout norms and display their corruption and partisanship for all to see, confidence in the Court has continued to slide.

And the Court really doesn’t seem to care.

Reporting uncovered that Justice Samuel Alito had an upside-down American flag (a symbol of alignment with MAGA’s “Stop the Steal” movement) flying at his home as well as a Christian Nationalist flag flying at another home of his—a signal of support for a radical strain of Christianity also aligned with Donald Trump. Yet Alito has refused to recuse himself from presiding over any cases involving Trump and his efforts to overturn the 2020 election and incite the Capitol riots.

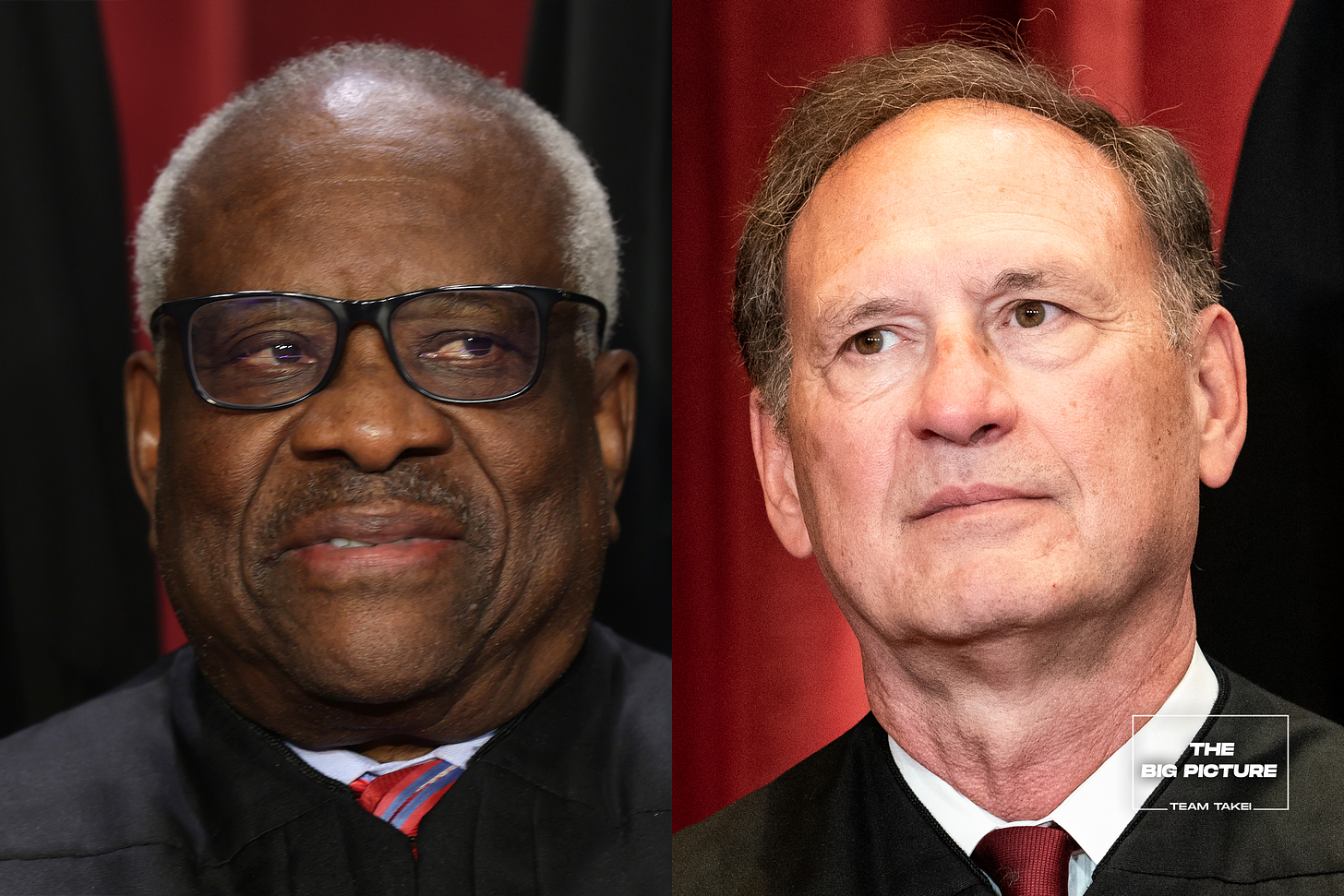

Alito’s defiance echoes Justice Clarence Thomas, who has similarly refused to recuse himself from Trump cases even though his wife Ginni was an active participant in Trump’s attempt to overturn a free and fair election in 2020.

And now Chief Justice Roberts is refusing even to meet with Senate Democrats to discuss judicial ethics.

So, is there anything Congress can do to rein in the Court? Is it possible to impose actual enforceable ethics rules? What are the options for reform of the Court being considered, and how likely are we to see real reform in the coming years? In today’s piece, I’ll explore these important questions.

The Roberts Court DGAF

Even before this year’s damning revelations, there was a crisis of confidence in the Supreme Court. Last year, ProPublica reported on multiple instances of Justice Clarence Thomas receiving luxurious trips and gifts from wealthy donors without disclosing them as required by law.

As ProPublica concluded:

Thomas appears to have violated the law by failing to disclose flights, yacht cruises and expensive sports tickets, according to ethics experts.

Many saw what followed from the Court as a largely performative gesture to address ethics concerns. On November 13, 2023, the Court unveiled its official “Code of Conduct.” But even in the language of the Code’s introduction, it was clear that the Court viewed the problem as a “misunderstanding” by others and that there was nothing wrong with the Justices’ own behavior:

“The absence of a Code, however, has led in recent years to the misunderstanding that the Justices of this Court, unlike all other jurists in this country, regard themselves as unrestricted by any ethics rules. To dispel this misunderstanding, we are issuing this Code, which largely represents a codification of principles that we have long regarded as governing our conduct.”

The condescending tone of the Court’s language here, plus the fact that the code was wholly unenforceable by any outside independent body, led The Brennan Center For Justice to conclude that this new “Code of Ethics” was “designed to fail.”

As they wrote the day after the Court’s new ethics code was released:

The Supreme Court has been the only court in the country without a binding ethics code. Now it has one of the country’s weakest. These new rules are more loophole than law.

The idea behind an ethics code is simple: nobody is wise enough to be the judge in their own case. Yet the justices will still judge themselves. There is no mechanism to enforce the code — no arbiter to enforce, apply, or even interpret these rules.

The Brennan Center was particularly concerned with the code’s section regarding “recusal,” which it described as follows:

The justices took the rule that applies to lower court judges but then inserted a handful of new loopholes, including one that could be so big that it swallows the rule — basically allowing a justice to disregard a required recusal if they think their vote is needed in the case.

And sure enough, mere months later, that prediction came true.

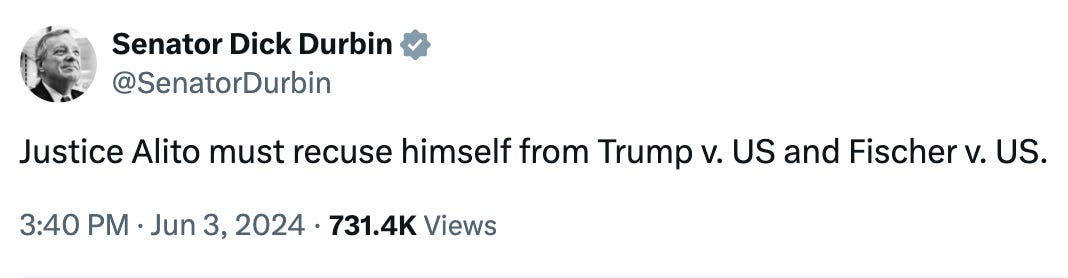

On May 17, 2024, in the wake of news that Justice Alito had flown an upside-down American flag outside his residence, Senator Dick Durbin, Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, called on Alito to recuse himself from Trump-related cases before the Court.

“Flying an upside-down American flag—a symbol of the so-called ‘Stop the Steal’ movement—clearly creates the appearance of bias. Justice Alito should recuse himself immediately from cases related to the 2020 election and the January 6th insurrection, including the question of the former President’s immunity in U.S. v. Donald Trump, which the Supreme Court is currently considering.”

Then, after the second Alito flag was reported, Durbin and Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, who is Chair of the Subcommittee on Federal Courts, wrote to Chief Justice Roberts urging him to compel Justice Alito to recuse.

“By displaying or permitting the display of prominent symbols of the ‘Stop the Steal’ campaign outside his homes, Justice Alito clearly created an appearance of impropriety in violation of the Code of Conduct for Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States (hereinafter Code of Conduct) that all nine justices adopted last year. He also created reasonable doubt as to his impartiality in certain proceedings, thereby requiring his disqualification in those proceedings as established by the Code of Conduct and federal law.”

This echoed a letter sent to Justice Alito by 45 House Democrats also urging recusal.

Shocking exactly no one, Justice Alito responded to the senators with a “thanks but no thanks,” and refused to recuse, asserting that “the two incidents you cite do not meet the conditions for recusal.”

He further argued:

“A reasonable person who is not motivated by political or ideological considerations or a desire to affect the outcome of Supreme Court cases would conclude that this event does not meet the applicable standard for recusal. I am therefore duty-bound to reject your recusal request.”

In a June 2 OpEd, Susan Sullivan, a former law clerk under Alito, repeated the calls for his recusal and laid out the stakes were he not to ultimately take the step to recuse:

Justice Alito may or may not be biased in favor of the former president, but the flag flying upside down at his home in the past unequivocally telegraphs reasonable questions about his impartiality in cases involving Trump. These questions, separate and apart from the crisis in confidence that such conduct may raise for the court, mandate Justice Alito’s recusal from these cases.

The gravity of the implications of Justice Alito’s refusal to recuse himself from these decisions cannot be understated. At stake is not only the independence of the court itself, but also its credibility, and its role as a protector of our constitutional democracy.

Between now and the end of the month when this term’s decisions are expected to be released, one can assume Justice Alito will not be changing his mind on the matter.

And even more disturbing, it appears no one can compel him to do so.

What Role Does Congress Have In Holding The Supreme Court Accountable?

A day after Justice Alito made clear he would not recuse himself from Trump-related cases, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote a letter of his own, responding to Senators Durbin’s and Whitehouse’s invitation to meet with them “as soon as possible” in order “to discuss additional steps to address the Supreme Court’s ethics crisis.”

But as Roberts sees it, there is no role for Congress when it comes to Supreme Court oversight.

As NPR reported:

“I must respectfully decline your request for a meeting,” Roberts wrote. He said that “apart from ceremonial events, only on rare occasions in our Nation’s history has a sitting Chief Justice met with legislators, even in a public setting (such as a Committee hearing) with members of both major political parties present.

He added: “Separation of powers concerns and the importance of preserving judicial independence counsel against such appearances. Moreover, the format proposed – a meeting with leaders of only one party who have expressed an interest in matters currently pending before the court – simply underscores that participating in such a meeting would be inadvisable.”

But Congress does have an oversight role. As Durbin and Whitehouse made clear in their request, they were appealing to Roberts not just as Chief Justice, but also

“in your capacity as…presiding officer of the Judicial Conference of the United States.”

Congress created the Judicial Conference over 100 years ago to frame policy guidelines for the administration of courts in the U.S. The Conference is headed by the Chief Justice and includes, among others, the chief judge of every court of appeals from every circuit.

While each branch of government is meant to operate as separate but co-equal ones, that’s not to say they don’t overlap. The Legislative Branch has a very specific accountability mechanism regarding the Executive Branch in the form of impeachment, so it’s absurd to suggest that a similar mechanism overseeing the Judicial Branch would somehow be unconstitutional.

As Justice Elena Kagan famously said during an appearance last summer:

“It just can’t be that the court is the only institution that somehow is not subject to checks and balances from anybody else. We’re not imperial.”

The Brennan Center laid out the role of Congress in a 2023 piece titled “Congress Has the Authority to Regulate Supreme Court Ethics – and the Duty” and subtitled:

From oaths to retirement to impeachment, Congress already regulates the high court, and it’s time for stronger safeguards against corruption.

The piece reviewed the well-established history of Congress overseeing the Court:

As the history of congressional regulation of Supreme Court ethics makes clear, it is squarely within Congress’s constitutional power to ensure the integrity of a coequal branch by holding Supreme Court justices to high ethical standards.

Since the founding, Congress has played a central role in regulating the ethical conduct of the justices, first by requiring them to take an oath written by Congress. Congress also sets the terms by which federal judges, including Supreme Court justices, retire and how they are compensated.

But almost a year later, while members of Congress have proposed legislative fixes, most of what we have to show for their attempts at oversight of the Court have been sternly written letters that simply go ignored.

And tweets.

To which people frustratingly reply:

Such a reaction is certainly understandable. Is there really nothing they can do?

Rep. Jamie Raskin, a Constitutional expert, in a recent New York Times OpEd reminded us that enforcing recusal is not optional. It is statutory, according to 28 U.S. Code § 455:

(a) Any justice, judge, or magistrate judge of the United States shall disqualify himself in any proceeding in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned.

And as Raskin makes clear:

The federal statute on disqualification, Section 455(b), also makes recusal analysis directly applicable to bias imputed to a spouse’s interest in the case. Ms. Thomas and Mrs. Alito (who, according to Justice Alito, is the one who put up the inverted flag outside their home) meet this standard. A judge must recuse him- or herself when a spouse “is known by the judge to have an interest in a case that could be substantially affected by the outcome of the proceeding.”

So what is Raskin’s prescription for compelling recusal?

The U.S. Department of Justice — including the U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia, an appointed U.S. special counsel and the solicitor general, all of whom were involved in different ways in the criminal prosecutions underlying these cases and are opposing Mr. Trump’s constitutional and statutory claims — can petition the other seven justices to require Justices Alito and Thomas to recuse themselves not as a matter of grace but as a matter of law.

The Justice Department and Attorney General Merrick Garland can invoke two powerful textual authorities for this motion: the Constitution of the United States, specifically the due process clause, and the federal statute mandating judicial disqualification for questionable impartiality, 28 U.S.C. Section 455.

As Raskin notes, the statute specifically cites “Any justice” in its wording, and the only “justices” in our system are sitting on the Supreme Court. So, for Raskin, it’s not an option for the Court to refuse reasonable recusal. He observes,

This recusal statute, if triggered, is not a friendly suggestion. It is Congress’s command, binding on the justices, just as the due process clause is. The Supreme Court cannot disregard this law just because it directly affects one or two of its justices. Ignoring it would trespass on the constitutional separation of powers because the justices would essentially be saying that they have the power to override a congressional command.

When the arguments are properly before the court, Chief Justice John Roberts and Associate Justices Amy Coney Barrett, Neil Gorsuch, Ketanji Brown Jackson, Elena Kagan, Brett Kavanaugh and Sonia Sotomayor will have both a constitutional obligation and a statutory obligation to enforce recusal standards.

Your move, Attorney General Garland.

It’s Not Just About Recusal, It’s About Reform

It is, of course, difficult to imagine anything changing during this term, even if the Justice Department were to intervene. And the fact is, the damage due to Alito’s failure to recuse himself has largely already been done. After all, Alito was on the Court, and his Christian Nationalist flag was flying high over his beach home in New Jersey, when it granted review of a case concerning the obstruction of Congress statute, one that could impact whether Trump himself may be charged with it.

And as Michael Waldman of The Brennan Center reminded us in a recent column:

Alito is part of the Supreme Court’s most egregious intervention on Trump’s behalf — its refusal to allow the timely federal prosecution of the former president. Special Counsel Jack Smith asked for a ruling confirming that Trump is not immune from prosecution in December 2023. Instead, Alito and his colleagues scheduled arguments for the last hour of the term and seemed to make up a doctrine of wide immunity for some criminal misconduct on the spot.

So what can be done in the face of such defiance? For Waldman, it goes well beyond simple recusal. The answer is substantive reform of the Court.

For one, Waldman believes it is essential that Congress pass a binding code of conduct for the justices.

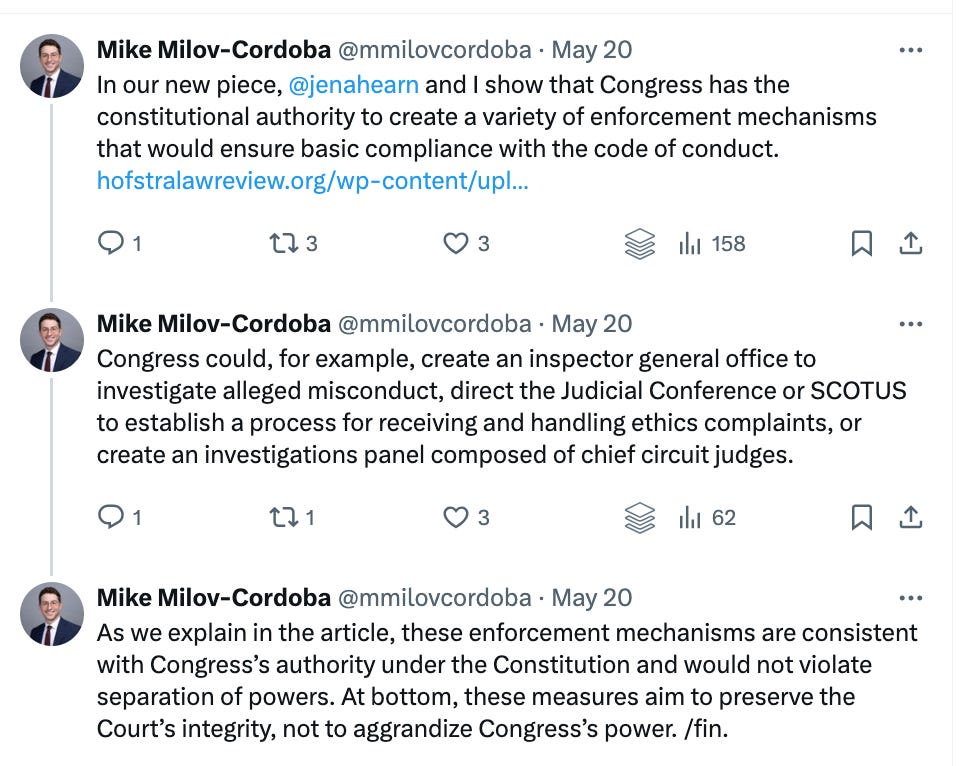

The Brennan Center’s Mike Milov-Cordoba laid out a basic enforcement mechanism Congress could set up to give the Court’s code of ethics some actual teeth in this X thread.

This is precisely what Senator Sheldon Whitehouse’s Supreme Court Ethics and Recusal, or SCERT, Act, which passed out of the Senate Judiciary Committee on a party line vote last summer, would implement. While Senator Schumer has not brought the bill up for a vote by the full Senate, Senator Whitehouse has revived his call for its passage in the wake of the Alito scandals.

Whitehouse’s Supreme Court Ethics, Recusal, and Transparency (SCERT) Act was advanced by the Senate Judiciary Committee last July. The bill would require Supreme Court justices to adopt a binding code of conduct, create a mechanism to investigate alleged violations of the code of conduct and other laws, improve disclosure and transparency when a justice has a connection to a party or amicus before the Court, end the practice of justices ruling on their own conflicts of interests, and require justices to explain their recusal decisions to the public.

Additionally, Waldman calls for term limits on the Court.

And, as we’ve said before, it’s time for term limits. In response to the latest scandal, Alito has shrugged. That is a powerful demonstration of the dangerously emboldening effects of lifetime power. Nobody should hold too much power for too long.

The Brennan Center laid out a compelling case for limits of 18-year terms for Supreme Court Justices, where after this length of active service, a justice would move to senior status, and a new justice would be appointed. You can read more about its proposal here.

To this end, Rep. Adam Schiff and Rep. Hank Johnson introduced the Supreme Court Tenure Establishment and Retirement Modernization Act (The TERM Act), which would, among other things, establish SCOTUS terms limits after 18 years and mandate regular nominations of Justices in the first and third year after a presidential election.

Additionally, a new Court Reform Now Task Force has been formed by House Democrats to, as member Rep. Jamie Raskin puts it:

“restore the Supreme Court’s integrity and fight to recapture public confidence in the Supreme Court — but right now, it’s a serious threat to the continuing work of constitutional democracy.”

On top of advocating for 18-year term limits and the passage of the SCERT Act, the Court Reform Now Task Force supports a 4-seat expansion of the Court to 13 total seats, matching the number of federal judicial circuits.

Here too Senate Democrats have introduced a bill, The Judiciary Act of 2023, which would expand the number of Supreme Court Justices to 13.

While Republicans like to frame such a proposal as “court packing,” the fact is they have already packed it, thanks to Senator Mitch McConnell and former President Trump.

As Senator Ed Markey, a co-sponsor of the bill, makes clear, the Judiciary Act would seek to undo that harm.

“Republicans have hijacked the confirmation process and stolen the Supreme Court majority—all to appeal to far-right judicial activists who for years have wanted to wield the gavel to roll back fundamental rights. Each scandal uncovered, each norm broken, each precedent-shattering ruling delivered is a reminder that we must restore justice and balance to the rogue, radical Supreme Court. It is time we expand the Court.”

Rep. Jamie Raskin eloquently broke down how these reforms would work during an interview with Slate’s Amicus podcast in May, making clear just how moderate a proposal these reforms actually are (watch at 18:21 below):

“So the Constitution, of course, does not fix the numerical composition of the Supreme Court. And it has changed nine or ten different times over the course of our history. We have 13 federal circuits. We’ve got nine justices…”

“We have entire federal circuits that don’t have a single justice. How about we start to talk about having 13 justices on the Supreme Court, one from each circuit, 18 year terms. They still get life tenure because they can go and be on the district bench or the circuit bench. Each president gets two appointments to the court, two nominations to the court, guaranteed nominations.

“Obviously, the Senate still has to advise and consent, but it will remove some of the toxicity and the poison from the nominations. If we know that each president will get two. And we can, you know, we can deal with this problem, but the current Supreme Court is just a scandal. It’s just a scandal.”

While such reforms may seem a ways off, since it appears even President Biden needs further convincing on Court expansion, there is value in shouting about the need for these reforms from the rooftops. It may be the only way to shift the public narrative about what should reasonably be on the table.

Before we can even consider these reforms, however, Democrats need to retake the House and build a robust Senate majority. Even then, it’s a multi-year project. But it’s well past time the left learned from the tactics of the right and made the Supreme Court an issue for every voter in every election.

Mainstream media isn’t focusing on the corruption of the Supreme Court, but we are. If you’re benefitting from reading about what’s really going on with Justice Samuel Alito and Justice Clarence Thomas, we hope you’ll support us by becoming a paid subscriber.

Every one of those justices were serving in the lower courts before SC so they already swore to uphold the law and live by a code of ethics at that time! it doesn't change because you moved up in a higher court!😳 it would really mean you have a higher standard of ethics to live by! Like not lying under oath! That should have been enough to kick each liar OFF THE BENCH, for life!

There should also be some rules about confirmations. McConnell held up Obama’s (because there wasn’t enough time …eight months) but then rushed Trump’s confirmation (less than a month) after the death of RBG.

I propose that if a president nominates a person for confirmation, the senate has a month to schedule confirmation hearings. If they do not, then the POTUS pick goes through without hearings.

And….senate only gets four rejections. They cannot drag it out in hopes of running out the clock. So if you pass on the first confirmation, just think what the next one will be. Senate may want to think more carefully.