Why Are Indigenous Mascots Still A Thing?

Despite numerous national and international organizations decrying the harm caused by them, people still cling to racist Indigenous mascots for sports teams.

Since the 1960s, the use of Indigenous American and First Nations names and images by sports teams as mascots has been the subject of increasing public scrutiny in both the United States and Canada.

But the issue is reported in mainstream media only in terms of Indigenous individuals being offended. This misrepresents the problem as one of just feelings and personal opinions held only by the targets and not tangible harm.

It also ignores the impact on non-Natives.

So what's the real issue with Indigenous peoples used as sports mascots?

We'll explore that today in The Big Picture.

— George Takei

I—like most people—grew up hearing stories about my heritage.

In most families, when passing on cultural heritage to the next generation, children learn what requires respect, what is sacred, what is taboo.

As an Indigenous child, I learned the struggles and sacrifices my ancestors made to preserve our culture. I learned how to treat regalia—traditional or ceremonial clothing—with respect.

I learned the importance of certain objects and symbols. I learned the tremendous diversity that exists between clans, tribes and nations among the Indigenous peoples of the United States and Canada.

My late Até (Father) was Oglala Lakota of the Oceti Sakowin. He was born on Pine Ridge Reservation in southwestern South Dakota. From age 5 to when he graduated at age 16 he was forced to attend Indian boarding school at Holy Rosary—a Catholic run school—also located on Pine Ridge.

Akenistén:’a (my Mother) was Kanienʼkehá꞉ka of the Haudenosaunee and Métis. She was born in Canada, but grew up with her adopted parents in Northern Maine from age three to adulthood after her Ista (Mother) died in childbirth. She was spared the Canadian Indian residential school system.

I learned to have pride in my culture on both sides of my family.

And then I began school and was introduced to things like this:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

We Don't Feel Honored

One of the first things people wanting to use Indigenous mascots say in their defense is they're honoring us.

My Tȟuŋkášila (Great-Grandfather) was a veteran of the battle at Peji Sla Wakapa—Greasy Grass for Lakota. The battle is often called Little Bighorn or Custer's Last Stand by others.

As a 15-year-old, Tȟuŋkášila Charlie Roan Bear earned a headdress. In 1912 he was photographed in his regalia.

Our family passed his regalia to the oldest male veteran until my Uncle Ralphie's children donated it to a museum.

As children, we learned a headdress was not to be touched or played with. It was a great honor to receive a headdress. We didn't even wear fake ones because it was disrespectful.

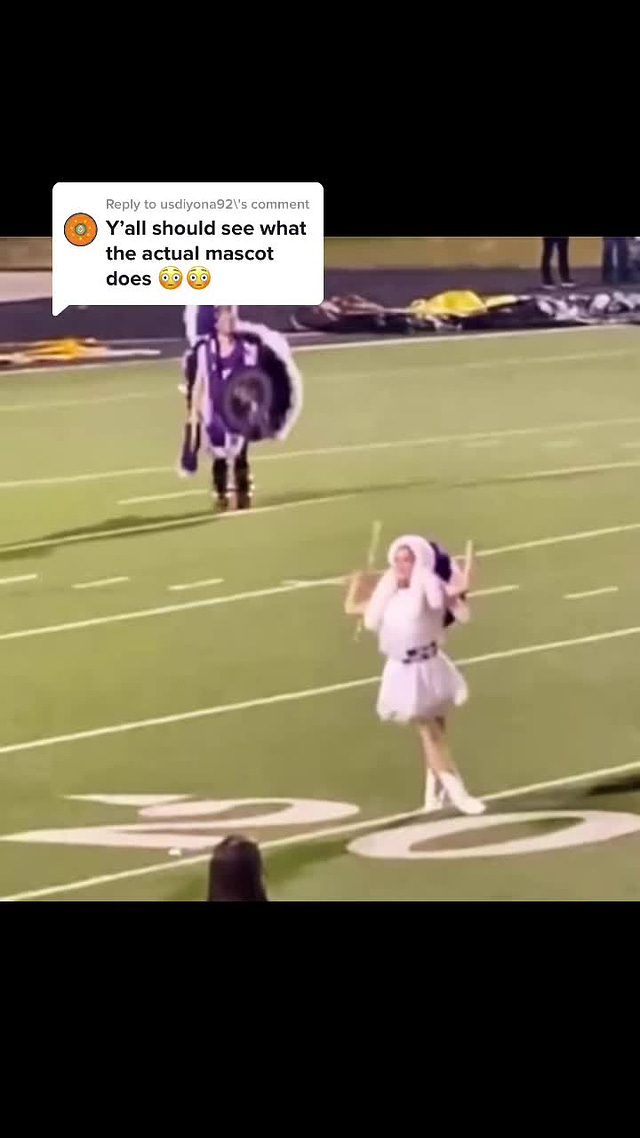

So how am I or my ancestors being honored by displays like this?

When people treat headdresses like they're hats or cheerleaders chant “scalp ‘em” or NFL football or MLB baseball crowds do the tomahawk chop, I feel anything but honored.

Defenders of Indigenous mascots as an honor refer to traits like a fighting spirit or being strong, brave, stoic, dedicated or proud. But these traits are based on stereotypes, not accurate Indigenous history.

It is embarrassing and demeaning to see this.

Or this.

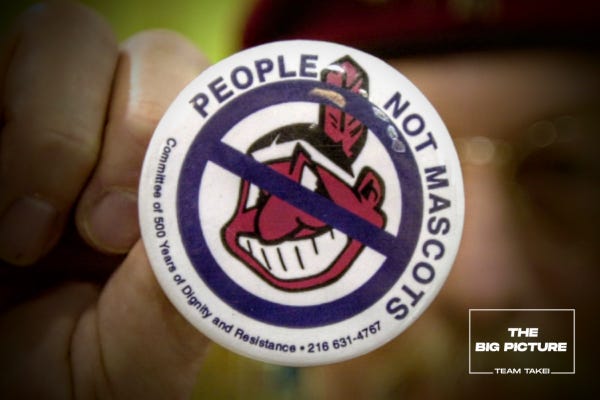

The Cleveland MLB team finally decided this honored no one and scrapped Chief Wahoo and replaced it with the Cleveland Guardians.

And no one died because of it.

How Very Dare They

The second thing we hear when we address our use as mascots is indignation that banning Indigenous mascots is taking a school or community’s traditions and heritage from them.

In the United States, Indigenous culture—including language, dance, song, clothing, art, and religion—was illegal until the late 1970s—less than 50 years ago.

But in the 1920s, schools and professional sports teams began adopting Indigenous identities as mascots.

During a period when the official government policy for Indigenous peoples was described as "kill the Indian, save the man," non-Natives were playing Indian using everything that had been stripped away from us.

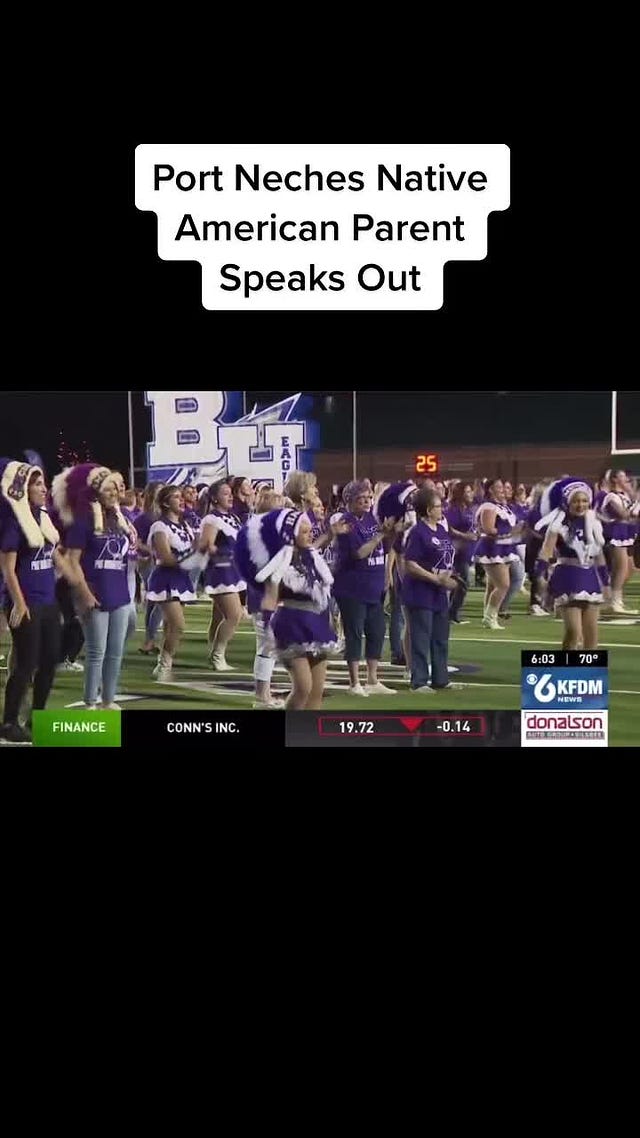

Yet when New York state decided to ban the use of Indigenous mascots, this was one Long Island school's response.

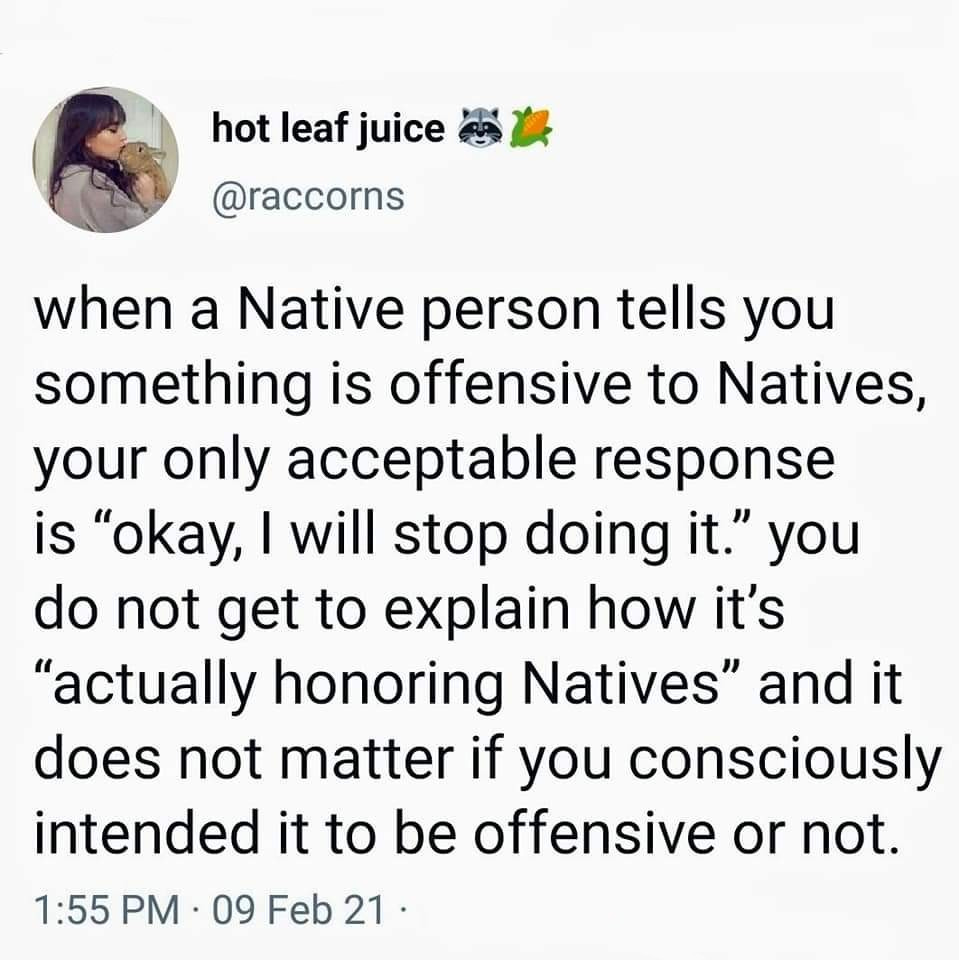

In my piece ‘But Where Are You Really From,’ I touched on listening to marginalized people.

I wrote:

“One tool I find helpful is to ask myself what I lose by stopping the behavior that was called out. Even if the person is being overly sensitive, what happens if I just acquiesce?”

“Do I really suffer any harm by agreeing with their request or does my ego just get bruised?”

“If it's just a bruised ego, I need to get over myself.”

It Doesn't Matter If They Know An Indigenous Person

The third thing we usually hear from proponents of Indigenous mascots is that they know someone who claims Indigenous identity and says they don't care.

You can find people in any culture unbothered by slurs.

But that doesn't negate the people who are.

Indigenous author and professor of Ojibwe Dr. Anton Treuer explained this well.

The National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) has a standing resolution—first adopted in 1998—opposing the use of Indigenous mascots.

NCAI is the oldest and largest national organization of American Indigenous tribes and nations and Alaska Natives. NCAI has campaigned since 1968 to end the use of Indigenous mascots.

Their resolution states:

“[T]he use of Native American mascots, logos and symbols depicting American Indian people are offensive to us, and such depictions are inaccurate, unauthentic representations of the rich diversity and complex history of the more than 560 Indian Tribes in the United States and perpetuate cultural and racial stereotypes[.]”

They added in 2005:

“The ‘warrior savage’ myth has plagued this country’s relationships with the Indian people, as it reinforces the racist view that Indians are uncivilized and uneducated and it has been used to justify policies of forced assimilation and destruction of the Indian culture.”

NCAI was established in 1944 “in response to the termination and assimilation policies the US government forced upon tribal governments in contradiction of their treaty rights and status as sovereign nations.”

We're Not A Monolith

I live in Northern Maine where—just like the Massapequa, New York school shown above—Indigenous mascots all wear feathered headdresses.

No tribe on Long Island or in Maine ever wore the style of regalia used by their schools’ Indigenous mascots.

A majority of Native mascots appropriate their overall look from the tribes of the Great Plains like the Lakota or Omaha—buckskins, beading, feathered headdresses. But then they borrow most of their design work from Southwest tribes like the Navajo or Pueblo or Pacific Northwest tribes like the Coast Salish or Haida.

Such homogenization leads to a subconscious belief that Indigenous peoples all look the same and we share a single culture and identity.

One need only think of how people in the United States view European countries like Italy, Spain, and Germany as having rich, diverse cultures while lumping the Indigenous peoples of the United States into a single identity to recognize the bias this creates.

Listen To the Experts

Studies show using Indigenous mascots lowers "the self-esteem of American Indian students."

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights has "called for an end to the use of Native American mascots in non-Native schools because they teach all students that stereotyping of minority students is acceptable."

The American Psychological Association publicly called for "the immediate retirement of all American Indian mascots," saying these "mascots are teaching misleading, and too often, insulting images of American Indians. These negative lessons are not just affecting American Indian students; they are sending the wrong message to all students."

When students and community members view Indigenous peoples in a cartoonish way, it enables the erasure of authentic historic and current Native culture.

It also validates bigoted speech or actions by adults and young people.

Indigenous-themed mascots are also opposed by the National Indian Education Association, National Education Association, American Sociological Association, American Counseling Association, NAACP, United Methodist Church, and the National Collegiate Athletic Association to name only a few of the many organizations who read the studies or did the research.

What Can We Do?

The National Congress of American Indians reported as of April 5, 2023, there were 1,901 schools in 966 school districts that use Indigenous mascots.

The Departments of Education or legislatures in New York (2023), Kansas (2022), Colorado (2021), Washington (2021), Nevada (2021), California (2015), Michigan (2012) and Oregon (2012) took steps to eliminate Indigenous mascots, but allow for exemptions.

To date, Maine (2019) is the only state to completely ban Native American-themed mascots.

Is your state on this list? If not, contact your state legislators and ask them to take action.

Is a school in your area still using Indigenous peoples as mascots? If so, contact your school board or district administration and ask why.

And when the debate over Indigenous mascots occurs, please, speak out.

~~~~~~~~~~

In addition to writing for The Big Picture, Amelia writes

I totally agree that all states need to ban non-native schools from having indigenous mascots. Public schools are using taxpayer dollars to perpetuate the stereotypes and hatred. This needs to stop.

Unfortunately it’s just another tool used by the colonizers to politicize and shame indigenous peoples in what they consider their place in the colonialists eyes! I’m sorry to say that, being a caucasien of European descent I’ve seen it in all its disgusting glory and I for one find it truly abhorrent that it’s perpetuated to this day! I have indigenous members by marriage in my family and I know they’re disgusted with it too! Indigenous peoples have a rich heritage and that should be respected and cherished and not turned into a cartoon or used as a prop for anything like the blatantly racist ways that it’s been done for hundreds of years! And yet it persists because of the blatant disregard for the facts that conquerors use to justify oppression! And it’s only going to get worse as the hatred’s and division grows in this country because of the culture war politics of the Republican Right continues! I’m a Transgender Woman and I know first hand how much vitriol and hatred these narrow minds can put out on a community that they deem inferior, but will continue to stand strong with my oppressed sisters and brothers no matter who or where they are from! Let Love Rule the world before we have no world to Love! 😢☹️🥰❤️