'But Where Are You Really From?'

Most people have heard the term microaggression, but what does it mean and how do these minor slights lead to major injustices?

The term microaggressions has been around since 1970. Many of us have heard the term, but do we know what it means?

And if we do know what the term means, do we understand the impact these slights and biases have on the affected communities?

Microaggressions are pebbles in the pond of society. The initial impact may be minor, but it does have a ripple effect.

How can we identify microaggressions and counteract them? That's what we will be looking at in today's The Big Picture.

~ George Takei

In 1970, Harvard University professor Chester Pierce coined the term “microaggression” to describe his observations of the subtle, everyday ways Black people experienced discrimination from their White counterparts. But its use has expanded beyond that original definition.

According to Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation by Derald Wing Sue, the term now refers to:

"Commonplace daily verbal, behavioral or environmental slights—whether intentional or unintentional—that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative attitudes toward stigmatized or culturally marginalized groups."

With that definition, the targets of microaggressions change based on the environment or dominant culture of a given situation.

We're going to focus on the United States because it's where I live as what my family likes to call an "ambiguously brown person."

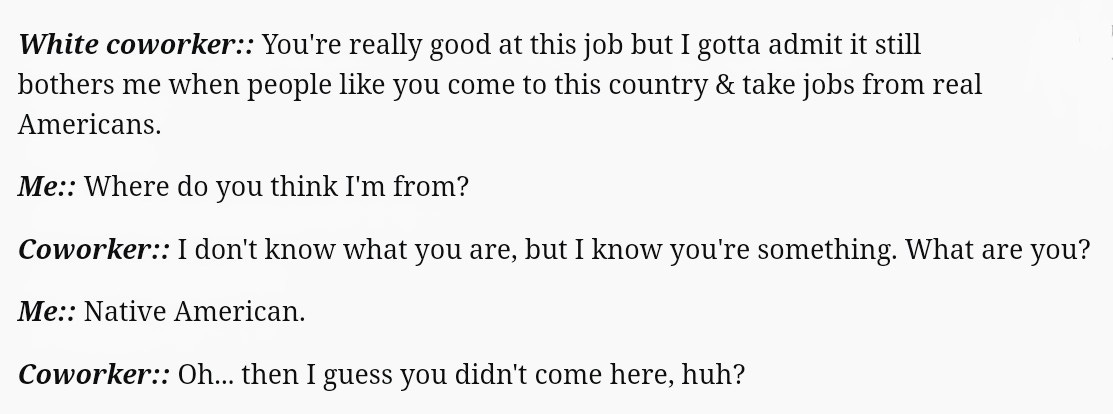

Or as a coworker once described me:

"I don't know what you are, but I know you're something."

So What Is a Microaggression in Plain Language?

Learning by example often works best, so let's go back to that aforementioned coworker.

I was in my early 20s and working as an account editor in an office of about 50 people.

One day, an older White gentleman who was one of my regular break time buddies shocked our lunch crew with this exchange:

Now while the rest of the table wasn't sure how to react, by age 20 I'd had years of experience. Humor and teachable moments were my go-to in most cases, especially when I knew the person meant no harm.

Despite his inappropriate comment at that moment, this man had always been kind and friendly towards me.

I responded:

"It's OK. It really bothered us, too, when people like you came here and took stuff away from real Americans."

Logically, people in the United States should realize brown people are Indigenous to the Americas and White people are not.

I reminded him of this fact, he acknowledged his error, and life went on.

Microaggressions Are Often Exclusionary

Most of us learned that United States history begins not at the formation of the United States in the late 1700s nor with the Indigenous cultures here for millennia.

U.S. history courses begin with inaccurate or outright fictionalized accounts of European imperialism and colonization at the end of the 1400s, almost 300 years before the creation of the United States.

The dominant culture spent several hundred years continuously messaging that “White, neurotypical, cisgender, heterosexual Christian” was the default setting for humanity. The dominant culture brands itself normal and everything else is either weird or exotic.

Most Americans view all Asian and brown people as foreigners.

Ken Tanaka's skit "Where Are You From" illustrated through humor what many Asian and ambiguously brown people—including Indigenous Americans—face on a regular basis because of this skewed view.

You can watch the video here:

When the woman turns the inquisitor’s own “But where are you really from” question—and the reaction to the answer—back on him, the absurdity is obvious. But those who ask such questions claim they're just trying to get to know people better.

That excuse doesn't pass the "would I ask a ___ person this same question?" test. In this case, he should ask himself if this same question and pushback is done with every White person he meets.

Based on his own reaction to the woman’s pushback, the answer is a clear “no."

He identified himself as "just a regular American” even though he stated his ancestry is based somewhere other than the United States.

But the woman said her great-grandmother was from Korea, making her a 4th generation American. But even so, the man insisted she wasn’t allowed to claim a Californian or "regular American" identity.

A frequent descriptor White people have chosen for me—even when they know I'm Indigenous—is how exotic my appearance is. Every man I've ever dated called me exotic as a compliment.

But I'm the exact opposite of exotic, which is defined as:

"originating in or characteristic of a distant foreign country."

In North America, I'm domestic.

White people are exotic.

Microaggressions Aren't Just Othering

I'm Indigenous North American. I'm also a cisgender, heterosexual woman—now over 50—and I'm on the autism spectrum.

For those keeping score, that's 2 checkmarks for the dominant culture and 4 against, so I've experienced a few microaggressions.

More than a few of them occurred in the workplace.

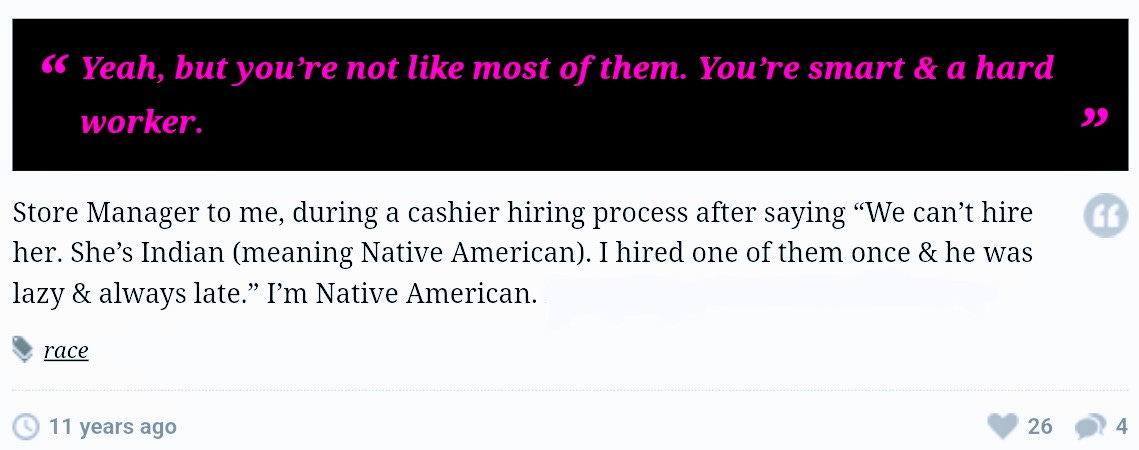

A few years after my lunchtime conversation I had changed jobs and worked my way up to the position of office cashier and interim assistant manager in a retail chain store.

My White male manager and I were reviewing job applications for cashiers when this happened:

I responded:

"I didn't realize that's how we're assessing applicants. Statistically speaking, we've had a 100% success rate with Asian and Black employees, a 66% success rate with Native employees, and a less than 25% success rate with White employees. So we should pull all the applications from White people out."

Was he displaying an unfair racial bias? Yes. Had he acted on it, would it have been racial discrimination? Absolutely.

But blanket judgments about minority communities based on one experience are so common that my manager thought nothing of doing it. And applying the same judgment to the dominant culture—even if statistically accurate—was something he never considered doing.

I had a good working relationship with him and he was the person who promoted me despite knowing I'm Indigenous, so I categorized his comment as inadvertent racism and responded accordingly.

For his part, my manager acknowledged and understood his mistake. He's still in retail management 30 years later at a higher level for a much bigger chain.

Hopefully our exchange stayed with him.

Microaggressions Are Often How Bigotry Sneaks In

In some cases, microaggressions are the visible manifestations of unconscious bias.

In my life I've had to deal with inadvertent racism, sexism and ableism almost daily. It doesn't take long to learn the difference between ignorance and deliberate bigotry.

Neither my coworker nor my manager was going to join a violent White nationalist organization. Neither was deliberately unkind to me during my time working with them—in fact both before and after the exchanges described here these men were very kind and considerate toward me.

But their biases unchecked could have led to real harm.

A person qualified for a job could have missed out on the opportunity. How many other Black or brown people also didn't get jobs because hiring managers had one bad experience with one of "those people"?

An identification of non-Whites as foreigners has allowed the public at large to turn a blind eye on internment camps, disregard for our own laws for asylum seekers, and the targeting of only brown immigrants and brown children in cages.

American poet and author Scott Woods wrote:

"The problem is that White people see racism as conscious hate, when racism is bigger than that. Racism is a complex system of social and political levers and pulleys set up generations ago to continue working on the behalf of Whites at other people's expense, whether Whites know/like it or not."

"Racism is an insidious cultural disease. It is so insidious that it doesn't care if you are a White person who likes Black people; it's still going to find a way to infect how you deal with people who don't look like you."

"Yes, racism looks like hate, but hate is just one manifestation. Privilege is another. Access is another. Ignorance is another. Apathy is another. And so on."

"So while I agree with people who say no one is born racist, it remains a powerful system that we're immediately born into. It's like being born into air: you take it in as soon as you breathe."

People recognize bigotry in rallies by hate groups, burning crosses, white hoods and Nazi symbolism.

But they often fail to recognize it in their own biases.

Because most White people see just genocide, lynchings and other extreme acts as the definition of racism, they're appalled by any suggestion anything they say or do is racist.

And they often respond accordingly.

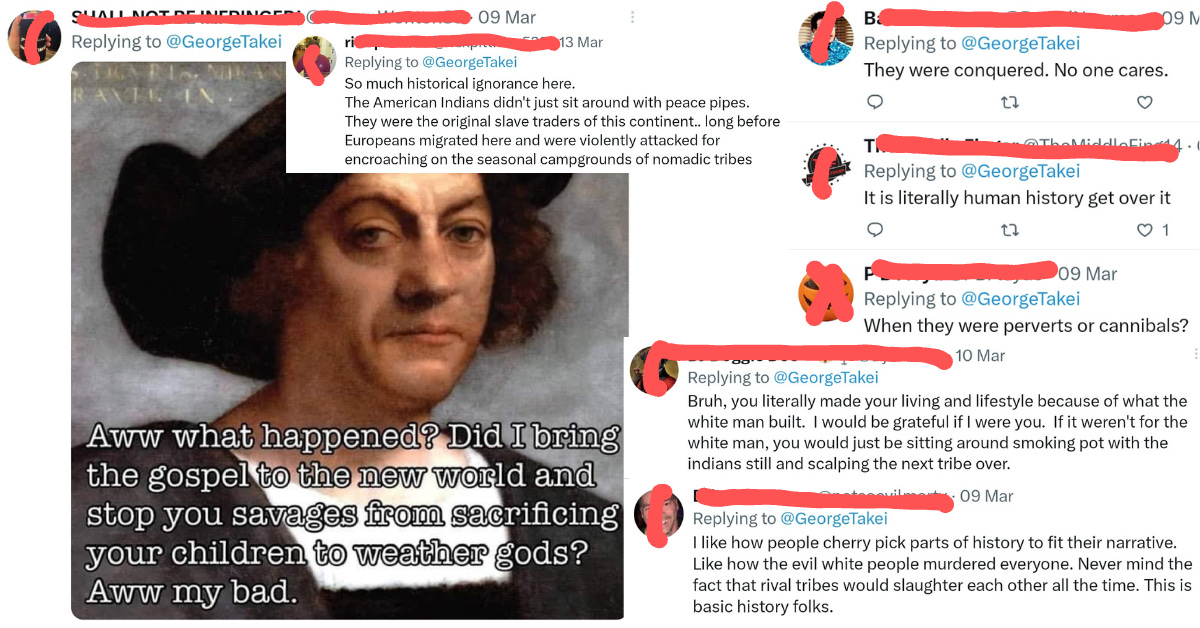

If I give a speech or write an article about Indigenous history, my own family's experiences, or—God forbid—the physical and cultural genocide in the Americas, most reactions will be empathetic and supportive.

But there are always plenty of angry White men on the attack, like these gentlemen—Twitter identities removed to protect the guilty—reacting to my piece addressing the crisis of Indigenous children in state foster care systems shared by Uncle George on Twitter.

Anytime I voice an opinion or share established facts online, I get a smorgasbord of White male vitriol including DMs full of threats of physical or sexual violence. It's not right, but after 53 years you get used to it.

People recognize this as racism because it's an extreme reaction.

But if I cite statistics and multi-year studies by medical, psychological and educational professional organizations and well-worded entreaties by Indigenous groups all asking Americans to stop using us as mascots for sports teams, suddenly the sympathetic masses are allying themselves with the angry White men they called racists.

Make no mistake, Indigenous mascots are racist, dehumanizing and cause real harm to our young people. Research has proven this. Our own experiences prove this.

So why is the reaction so different?

Because the racism is largely inadvertent—no organization picked its mascot with a goal of causing harm. And many well-meaning allies have used these mascots for years and they can't imagine themselves in the same category as those angry White men they called racist.

Microaggressions are often the same.

And the reaction to them being called out is similar. Suddenly the spotlight isn't on that guy over there, it's internal.

Calling yourself out is never easy. But to be a better ally to marginalized people, it's necessary.

To go back to Scott Woods commentary on racism, he added:

"[Racism is] not a cold that you can get over. There is no anti-racist certification class."

"It's a set of socioeconomic traps and cultural values that are fired up every time we interact with the world."

"It is a thing you have to keep scooping out of the boat of your life to keep from drowning in it."

I'm part of several marginalized groups. Many of us are, as women or people with disabilities. But I'm also part of the majority as a cisgender, heterosexual person.

I need to check myself, too, when it comes to interacting with people marginalized because of their gender identity or sexuality. I don't get a free pass because I too am marginalized or because "some of my best friends" are trans, non-binary or gay.

If they tell me something I say or do is problematic, I need to avoid the impulse to defend myself.

I don't need to provide testimony of my friend who is also gay or trans or non-binary who doesn't have a problem with it—as far as I know because my friend may just be tolerating my ignorance to spare my feelings.

It's not about me.

One tool I find helpful is to ask myself what I lose by stopping the behavior that was called out. Even if the person is being overly sensitive, what happens if I just acquiesce?

I also need to recognize that while my one infraction may look like "no big deal" from my perspective, this person has probably dealt with this over and over again. Do I really suffer any harm by agreeing with their request or does my ego just get bruised?

If it's just a bruised ego, I need to get over myself.

Sometimes Microaggressions Are Used For Deliberate Harm

As I've noted, dealing with microaggressions is a lifelong exercise for marginalized people. You get used to it and you develop strategies for dealing with it.

I always ask myself:

Is this a teachable moment?

Is this coming from a person I care for or respect?

Will I ever need to interact with this person again?

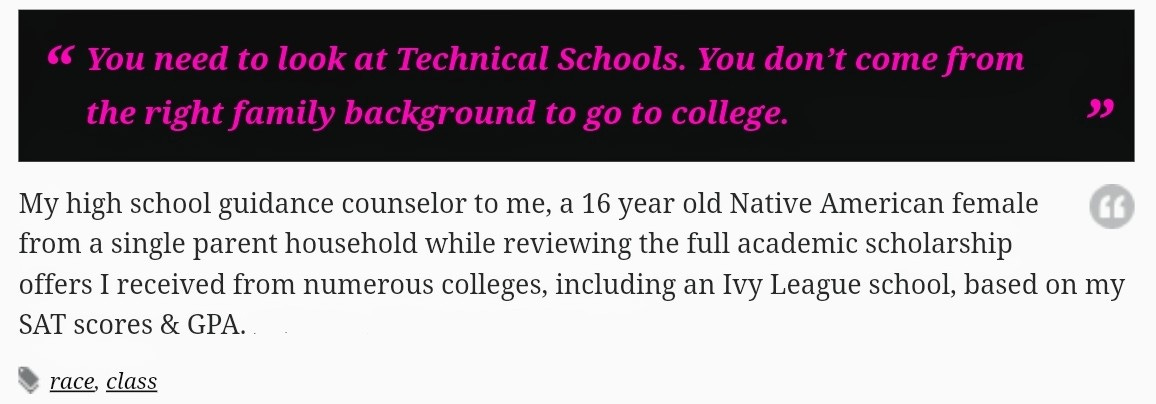

In my high school in a small town in Northern Maine, I wasn't from the right family to be successful. So my academic success was viewed negatively by my guidance counselor and the school administration.

After taking the SATs after my freshman year, I started getting recruited by some well respected schools. By the time I was a junior I had a lot of options. When it came time to choose, my guidance counselor made sure I knew I didn't belong at any of these schools.

He called me into his office for this exchange:

This wasn't a teachable moment.

This middle-aged White man had made it clear many times he was not open to my perspective. It was time to take a different route, which eventually included the school board and the school district demanding and paying for extensive IQ testing to "prove" I wasn't smart.

Don't try to make sense of that logic.

It didn't make sense then and it didn't work out the way they hoped.

Oops.

Because some microaggressions are based on deeply held bigotries, people who react out of ignorance—what I call inadvertent bigotry—are sometimes accused of ill-intent.

And some targets of microaggressions are also no longer willing to parse out intent. I choose to do so because I have the bandwidth and thick hide to do it. I also have a good support system where we laugh with each other about the ignorant things people say to us daily.

But marginalized people don't owe their time or energy to educate the masses.

And microaggressions are pervasive in our culture.

They show up on TV shows, in movies, in books, in how we're taught history, in how we're trained to interact. For individuals with intersectional marginalized identities it can feel like constantly being attacked while to the microaggressor—yes, I made up a word—it was just a one-off comment and no big deal.

Why is someone biting their head off?

Microaggressions are also usually the focus of diversity training. The companies that get paid to create the training usually compile all the complaints "diverse" people made and put them in skits and videos without context.

The reaction to this training is often very negative.

People feel attacked over nothing. They wonder why everyone is so sensitive and ask if people are looking for things to be mad about.

Newsbroke-AJ+ did a great job of addressing this in their comedy sketch "White Fragility In The Workplace."

The video is filled with examples of microaggressions and the reactions marginalized people are used to seeing when they call them out.

The Bottom Line

Microaggressions are going to happen. They're inserted into our psyche almost from birth by media and interpersonal relationships. They're the result of the biases, stereotypes and misconceptions we absorb.

We can't stop them, but we can alter how we react to them as both the microaggressor and the target.

Being a good ally is listening without ego when the community you're supporting calls you out.

It's saying:

"I'm sorry. I didn't know. Thank you for telling me. I'll try to do better."

As a target, if you've got the ability, the bandwidth and the support system you can educate your allies and report the bigots.

We're better together as equally valued, diverse beings.

Let's try to get there.

~~~~~~~~~~

In addition to writing for The Big Picture, Amelia writes

It might help at least the cis-female-white readers of this to reflect on their own experiences of this phenomenon. I recently discovered that Ruth Bader Ginsburg had exactly the same experience I did when I was in a male-dominated corporate world: at a meeting (often the sole female) I would make a point or suggestion that was completely ignored--until a male made the same comment, often in the same words, and everyone applauded. Certainly not all these men were openly sexist (a couple of them were) but they just couldn't HEAR a woman making sense.

Or a husband agreeing to "babysit" while you finish a brief.

I'm not saying these are at the same level as the microaggressions experienced by minorities of any race or gender. I'm just saying that if "majority" women just reflect on their own experiences they are much likelier to agree that such microaggressions are demoralizing and not something anyone has to swallow as a "permission" to belong to American culture.

Microaggressions are situational and I've really enjoyed the feedback from readers on my piece.

I'd love to hear from some men.

For example, a dear friend I've known 40 years now is an award winning elementary school teacher in K-3 classrooms for decades. He gets a LOT of well-meaning microaggressions and not so well-meaning ones because of his gender and chosen profession.