Why The Indigenous Genocide In America Never Ended

Foster care took over where boarding schools left off with Indigenous children, so the Indian Child Welfare Act was passed. But now that protection is under attack.

Like many of you, when I think of the term “Indigenous genocide” I picture events from centuries ago when Native populations first encountered European colonizers and their diseases and weapons of war. In our history textbooks, we learned European settlers pushed westward, displacing Indigenous tribes until sadly they were no more.

But this is wholly inaccurate.

The “Indians”—as Columbus infamously misnamed them—are still here in America. They number well over five million according to the 2020 census.

And yet, as hard as it is to admit, a genocide of Indigenous people and cultures continues in this country even to this day, as Native children are removed from their families and tribes to live in primarily White, Christian homes. That continuing assault is today’s subject in The Big Picture.

— George Takei

Beginning in 1879, hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children in the United States were forcibly removed from their homes and shipped to boarding schools run mostly by religious orders under contracts from the federal government.

This policy of removal continued the government's aim of Indigenous genocide—beginning with bloody massacres but moving forward with forced family and cultural separation.

My own paternal Great-Grandfather was shipped as train freight from South Dakota to Haskell Indian Institute in Kansas in the late 1880s. The rest of my paternal family were forced to attend Holy Rosary boarding school in South Dakota until my generation.

But the damage to Indigenous families is not a thing of the past—it continues to this day in a different form:

Foster care.

Indigenous children were so overrepresented in state foster care programs that the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) was enacted in 1978 to combat the problem.

The intent of the act was to ensure Native children were not lost to state child welfare agencies. It set provisions to ensure the child’s tribe is notified of state child custody proceedings and gives tribes legal authority to intervene.

According to the work of Carol Locust in her 2000 Split Feather study:

"Indigenous children adopted as infants from their tribal communities and families suffered as adults with emotional, psychological and spiritual issues."

"As a direct result of the loss of cultural experiences and the transmission of a cultural identity, their psychological and emotional wounding had lifetime consequences."

While ICWA hasn't been completely effective due to state noncompliance, it did create a significant drop in the number of Indigenous children in foster care.

But there have been legal challenges to ICWA—mostly from the religious right. Now one of those challenges is before the Supreme Court in Brackeen v. Haaland.

A History Of Genocide

The first phase of the genocide we should know from snippets from our history books.

From the beginning of European contact, the policy towards Indigenous populations was exploitation then death. Colonizers and then settler governments at first cooperated with Indigenous tribes to ensure their own survival or profit.

But once Indigenous existence became a problem because they competed for resources, any prior cooperation, backed by legally binding treaties between nations, devolved into extermination of the so-called "merciless Indian savages."

What is less understood is that after several high profile massacres in the late 1800s, which included the brutal murders of Indigenous women, children and elders, President Andrew Jackson's credo of "the only good Indian is a dead Indian" was replaced in official U.S. government policy with an effort to fully assimilate Indigenous peoples into White, Christian culture.

As Carlisle Indian School founder Captain Richard Pratt once stated:

"A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one, and that high sanction of his destruction has been an enormous factor in promoting Indian massacres."

"In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man."

Thus was the policy of Indigenous extermination replaced by Indigenous assimilation.

In the late 1800s, Congress passed laws making Indigenous cultural and spiritual practices illegal. And at the boarding schools, children were forbidden to keep any portion of their family and tribal traditions. Surviving records from these schools show that beatings, starvation or confinement were meted out as punishment for any infractions.

Many children suffered physical and sexual abuse at the hands of their caregivers and deaths were common. Entire generations were lost to their tribes. Children were routinely loaned, sold or adopted to White families by the schools either as a novelty or a laborer.

By the 1960s, the American civil rights movement came to Indian Country and tribes demanded an end to boarding schools. This spared me and my sisters. Most schools closed or were turned over to tribal control by the early 1990s.

To counter widespread Indigenous cultural destruction, in the 1970s Congress repealed the laws enacted to forcibly assimilate Indigenous peoples. In 1978 it passed the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) allowing Indigenous families and tribes a say in the welfare of their children.

So how is the genocide still ongoing in 2023?

By The Numbers

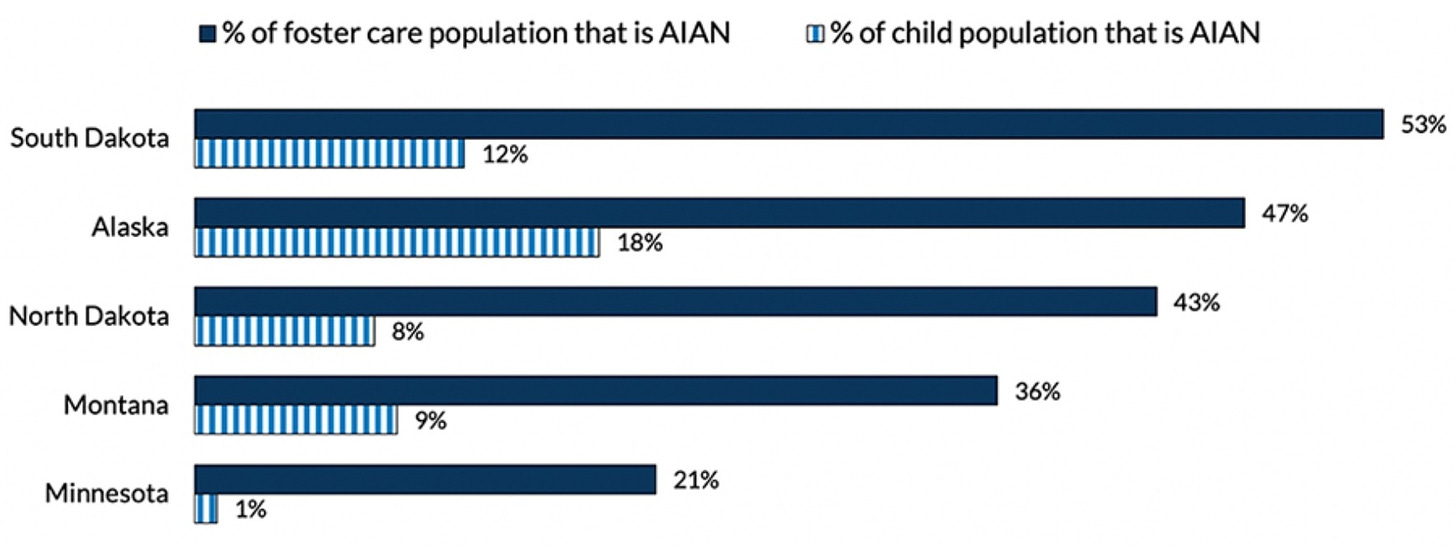

Indigenous peoples in the United States remain up to four times more likely to have children taken and placed in foster care than non-Indigenous parents. In 2020, the Oklahoma Department of Human Services reported Indigenous children made up over 35 percent of kids in foster care, but Natives made up only about nine percent of Oklahoma’s population.

In the 10 states with the highest populations of Indigenous children in 2020, Native children were overrepresented in foster care in nearly every state. Within those 10 states, the disproportionality of Indigenous children in foster care was highest in South Dakota, Alaska and North Dakota.

In 2020 in South Dakota Indigenous children were only 12 percent of the overall child population in the state but comprised 53 percent of the children placed in South Dakota's mostly privately run, for-profit foster care system.

As Citizen Potawatomi Nation FireLodge Children & Family Services Foster Care/Adoption Manager Kendra Lowden stated:

“That is the definition of racial disproportionality."

While ICWA was enacted to address such disparities and add protections, numerous factors continue to impact the unequal rate of Native children in state foster care systems.

Importance Of The Indian Child Welfare Act

As discussed above, Congress addressed Indigenous cultural genocide by repealing old laws banning cultural and religious practices and then passing others designed to safeguard Native existence. One such new law was ICWA.

That law's stated purpose is:

"...to protect the best interest of Indian Children and to promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families by the establishment of minimum Federal standards for the removal of Indian children and placement of such children in homes which will reflect the unique values of Indian culture."

Some of the major provisions of ICWA (USDHHS, 2015) are:

Established minimum federal standards for the removal of Indigenous children from their families.

Required Indigenous children to be placed in foster or adoptive homes that reflect Native culture.

Created exclusive Tribal jurisdiction over all Indian child custody proceedings when requested by the Tribe, parent or Indigenous “custodian” (except in cases where such jurisdiction is contrary to other Federal law, e.g., P.L. 280).

Granted preference to Indigenous family environments in adoptive or foster care placement.

Required State and Federal courts to give full faith and credit to Tribal court decrees.

Before ICWA—according to data compiled by the National Indian Child Welfare Association—about 80 percent of Indigenous families living on reservations lost at least one child to state run foster care systems.

Additionally, more than 25 percent of all Native children were seized from their parents by state governments. Approximately 85 percent received placements with non-Native, almost exclusively White families.

In almost all cases, no attempt was made to place the children within their tribes.

Despite reunification and preservation of families supposedly comprising a cornerstone of the foster care system, Indigenous relatives were routinely denied custody of Native children who were removed from their parents' custody. ICWA was intended to force state foster care systems to address this discrepancy between their stated policies and their practices regarding Indigenous families.

Opponents of ICWA claim that it is reverse racism targeting White foster or adoptive parents. But proponents argue ICWA just made standard practices—like preserving the family—applied to the majority of children in foster care applicable to Indigenous children.

ICWA also recognized the sovereignty granted by the federal government to individual Indigenous nations. It is illegal, for example, for the United States or a state government to seize custody of a child where their relatives are citizens of a foreign nation and are demanding return of the child.

The case of Cuban refugee Elián González illustrates this custody requirement for minor children well: When his Cuban father demanded Elián’s return after his mother's death, the State Department complied.

In accordance with federal law, Indigenous nations recognized by the federal government are sovereign nations. The same legal perspective applied in the González case should apply to tribal nations within United States borders regarding the custody of minor children.

Yet state governments routinely ignore ICWA and tribal rights of child custody.

A Problem Of Perspective

In 2023, Indigenous children in the United States are still overrepresented in foster care. And despite the enactment of ICWA, the practice of removing Indigenous children from their families, relatives and communities and placing them in foster care with or adoption by White families remains an ongoing problem.

Family fostering is the norm in Indian Country, but states don't recognize that fact. In my father's tribe—Oglala Lakota of the Oceti Sakowin—your father's brother is also your father, not your uncle. His children are your siblings, not cousins.

Your mother’s sister is also your mother, not your aunt. Her children are your siblings, not cousins.

Everyone you share blood with or who marries into the family is your cousin with no distinction between first, second, third, etc… Older cousins as well as your father's sisters and your mother's brothers are your aunties and uncles.

At any time for any reason, an Indigenous child can go stay with any one of their family Elders, other fathers or mothers, aunties, uncles or cousins. No advance notice or permission is required because it's understood the entire family is responsible for child welfare, not just the birth parents.

But state child welfare seizes children because they're not with their birth parents based on a White-centric view of family and community.

Said CPN Family Services' Lowden:

"And that was even if there was no abuse—there were no issues occurring."

"Even if there were willing and fit family members available, these children were still adopted out to White families."

White-centric standards are applied to evaluations of Indigenous family dynamics, living situations and cultural practices by a dominant culture with a long history of defining their own culture as "normal" and any deviations as unacceptable.

ICWA contains a provision for states to treat tribal foster homes according to the tribes’ standards of cultural norms such as extended families raising children and housing types and conditions.

But federal enforcement of ICWA is sorely lacking.

States claim they're forced to place Indigenous children with White families because there aren't enough licensed Indigenous foster parents.

But if states didn't disproportionately seize Indigenous children and placed children with relatives, as evidenced by the numbers shown above, the shortage wouldn’t be an issue.

It's a self-created problem for states that struggle with following ICWA guidance.

Who Defines What's Best For The Child?

The original purpose of ICWA was to address the harm caused by the federal government's assimilation efforts—the removal of children from their culture.

But assimilation was viewed by the majority White population as a benefit to Indigenous peoples because it dealt with the supposed savages humanely.

In other words, it beat the alternative.

When Army personnel at the Sand Creek massacre of November 1864 balked at murdering unarmed Cheyenne and Arapaho women and children, Colonel John Chivington declared:

“Damn any man who sympathizes with Indians!... Kill and scalp all, big and little; nits make lice.”

Historians believe the death toll was about 150 with two-thirds being women and children—even infants. Soldiers were told to use swords, bayonets and their boot heels to save bullets.

A series of such Army massacres followed, but photos of the mutilated bodies of women, children and the elderly soured public sentiment about the federal government's extermination policy for tribal nations.

Providing an education and tools for Indigenous children to enter White society was deemed the best solution. Any Indigenous child given the privilege of living in a White, Christian home was far better off than any living on a reservation with their heathen parents.

That racial and religious bias still influences Indigenous child placement decisions.

White Christian Nationalists—Major Challengers of ICWA

The plaintiffs in Brackeen v. Haaland before the U.S. Supreme Court during the latest session argue that ICWA is unconstitutional because it's racially biased against White parents in foster care and adoption of Indigenous children.

It is no coincidence that the Brackeens—a White Texas couple trying to adopt a 4-year-old Navajo child—are presented to the media as a good, Christian family. They made clear they attend an Evangelical Church of Christ congregation twice a week and cited their Christian faith as part of their motivation to adopt.

The Brackeens said they felt called by God to adopt, telling the New York Times in 2019 they considered adoption a way to “rectify our blessings.” They're backed by numerous Evangelical Christian organizations.

In an amicus brief, anti-ICWA group the Christian Alliance for Indian Child Welfare (CAICW) wrote:

“For nearly fifty years, ICWA has imposed race-based classifications on Indian children and their families—a clear violation of Equal Protection—and has caused horrendous individual suffering as a result.”

CAICW’s public Facebook page regularly shares stories about what they see as the depravities of Indigenous culture. Their group believes all Indigenous children would benefit from placement with White, Christian families over remaining within their own culture.

But critics note this continues a long history of White Christian efforts to convert Indigenous children and remove them from their homes and families.

Minnesota Indigenous Democratic state Representative Heather Keeler [Yankton Sioux] faced backlash from her Republican colleagues after speaking out about right-wing Christian targeted efforts to adopt Indigenous children. The post was later deleted.

Keeler posted online:

"I’m sick of White Christians adopting our babies and rejoicing. It’s a really sad day when that happens. It means the genocide continues.

"If you care about our babies, advocate against the genocide."

"Help the actual issues impacting Indigenous parents, stop stealing our babies and changing their names under the impression you are helping."

"White saviors are the worst!"

Minnesota Republican Party Chairman David Hann countered in a statement:

"There is no place in our political discourse for attacks on Minnesotans’ race or religions."

"We condemn this hateful and extremist rhetoric in the strongest possible terms and call on all Democrats to do the same."

But ICWA proponents draw a direct line from Brackeen v. Haaland to past efforts to separate Indigenous children from their parents—along with their cultures and spiritual practices—going back to the federal Indian boarding school system.

Many of the people spearheading those former efforts were also motivated by their Christian faith.

CAICW is joined in the fight to abolish ICWA by Nightlight Christian Adoptions. The Evangelical Christian adoption agency advocates adoption as a boon to Christianity.

According to a brochure promoting their practices, Nightlight Christian Adoptions stated:

“Adoption is one of the most effective ways to make disciples of all nations.”

Christian nationalists often cite religious freedom as justification for their actions. But theirs is not the only religion to consider.

Arizona State University law professor and tribal judge Robert Miller [Eastern Shawnee Tribe] stated:

"This absolutely is about culture/religion."

"It’s about raising your citizens for the future to preserve your language, your cultural practices. You and I could easily put the category of religion on that."

What Can Be Done?

As Donna Butts of Generations United wrote:

"We can look to Canada, which continues modeling the critical role of acknowledging past injustices, changing discriminatory policy and making reparations."

In other words, the first step to fixing a problem is admitting you have a problem.

Canada acknowledged their long, cruel history of needlessly removing First Nations children from their homes and cultures. On April 1, 2022, Canada implemented immediate measures to help reduce the number of First Nations children in foster care.

They also approved a $40 billion (CA) settlement for reparations and reformation.

Pressuring the United States federal and individual state governments to identify and address racial, cultural and religious biases is one solution.

Asking state officials if ICWA's provisions are being followed is another.

In 2020 the Maine Democratic platform adopted a provision to uphold existing tribal treaty rights as well as other tribal rights, including ICWA. Prior platforms stated only a vow to "work with" tribal governments.

You can also support organizations like NICWA that advocate for Indigenous children.

Per their website:

"Our vision is that every Native child must have access to community-based, culturally appropriate services that help them grow up safe, healthy, and spiritually strong."

"NICWA accomplishes this by helping tribes and other services providers implement programs that are culturally competent and draw on families’ strengths."

The survival of Indigenous peoples in the United States is always dependent on the next generation. Tribes have survived—against overwhelming odds—a series of government sanctioned genocides.

It's time for the weaponization of foster care to end.

*****

UPDATE: On June 15, 2023, the United States Supreme Court issued their ruling in Brackeen v Haaland.

In a 7-2 decision, the SCOTUS reaffirmed the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act.

In response to the ruling, Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. stated:

“Today, the Supreme Court once again ruled that ICWA, heralded as the gold standard in child welfare for over 40 years, is constitutional.”

“Today’s decision is a major victory for Native tribes, children, and the future of our culture and heritage.”

~~~~~~~~~~

In addition to writing for The Big Picture, Amelia writes Auntie Mavis’ Musings

By the time I got to the end of this article all I could do was take deep breaths to slow my outrage. I've long dwelt on the fact that the United States of America in which I grew up was in reality based on a genocide, but this article (and I admit recent viewing of the Yellowstone prequel, 1923) have brought me awareness of how much deeper and ongoing that genocide is. I'll skip my outrage at the hypocrisy of the so-called "Christians" behind this, but the 2023 reach of the "Christian Nationalist" movement is increasingly outrageous and infuriating. I'm deeply saddened and increasingly disillusioned with Christianity and the country I grew up believing in. I will add this cause to the long list of issues for which I've sought to advocate. I may not be able to do much, but I'll do whatever little I can.

I knew about the past horrific actions of the US government and US religious groups against indigenous communities. I was not aware of the continued horrific actions as regards US foster care. This is shameful and must stop. How can we be a nation of laws when we habitually ignore our treaties with the indigenous tribes. Thank you so much for writing about this and for providing links to groups that work against these actions. I truly do not understand this hatred, and there is nothing about it that is Christian, but it has to stop.